The Waterwheel Saga – Sugar and Rum

A waterwheel was one of the most efficient sources of power to drive the mills.

Rum manufacturing originated in the Caribbean almost by accident. In the early 1600s, Spanish and Portuguese seamen transported sugar cane from the Canary Islands and Madeira to the Caribbean islands. Labour was a vital commodity at this time, and new world settlers used it for transportation, cooking, industrial activities, or simply producing drinkable liquor. Sugarcane has been grown here for just as long. Its scarcity affected both the opportunity and motivation for numerous historical events.

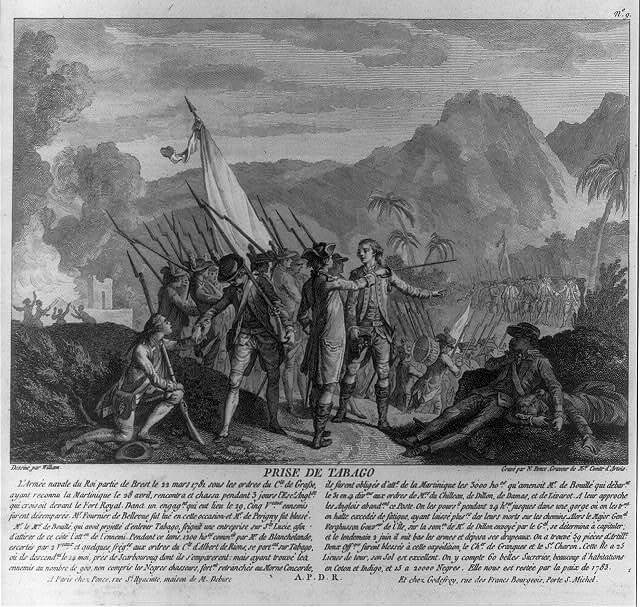

A robust sugar industry existed in Tobago, one of the southernmost islands of the West Indian archipelago, which is now part of the twin-island Republic of Trinidad and Tobago since 1962. The sugar trade of Tobago began considerably earlier than that of Trinidad, in 1665 when the Dutch introduced it.

When British planters first arrived on Tobago, given its size and location, they expected to find a barren wasteland; instead, they discovered a lush and green country ideal for colonization. As a result, the colonists selected and purchased lots according to their favourable and bad characteristics – steep slopes, deep forestation, shipping access, health issues, and water availability.

Tobago is considered a gem among islands and became a battleground for European (Dutch, English, Swedes, Courlanders (Latvians) and French) colonists in the late 1500s and early 1600s. However, colonists did not export sugar until 1763, when the British occupied the country, and it rapidly became the principal crop. The enormous profits made in the 1790s led to the term “as rich as a Tobago planter” in London.

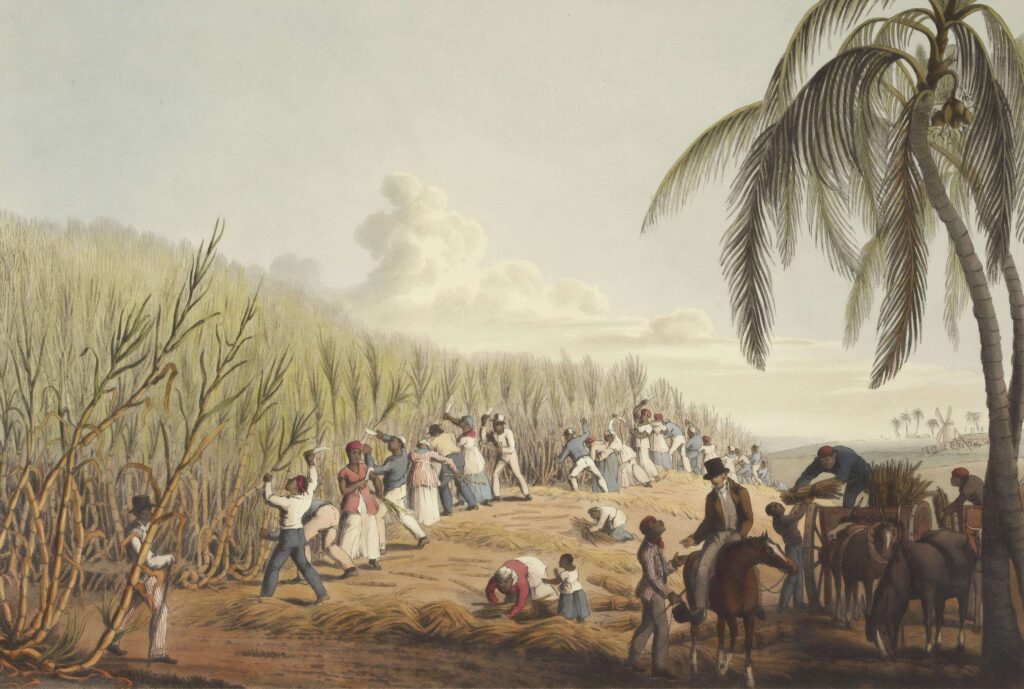

The island changed hands 31 times before being ceded to the British in 1814 under the Treaty of Paris. Thousands of enslaved Africans were taken from Africa and traded to the West Indies to work on the plantations.

Although the practice has gotten considerably more efficient in recent years, rum making was once a cumbersome process involving fermenting molasses – the by-product of sugar refining over long periods. It was hard and intensive work. Distillers then used the molasses imported to England to produce rum in cities close to the shipping ports, such as Bristol and London. Rum distillers took a conscious effort to develop and perfect the methodology for barrel-ageing rum. As the quality of rum improved, the demand for aged rum skyrocketed.

Rum is said to have originated in the West Indies, according to evidence. In 1650, in Barbados, rum was first documented in the writings of Richard Ligon, a loyalist that fled England for Barbados during the Civil War. Although the origin of its name was lost, Ligon referenced it as “kill-devil” and others like “rumbullion,” meaning “uproar”. The Malays call it Brum. By 1667, there were many names associated with the intoxicating beverage, but the title “rum” remains to this day.

“There’s naught, no doubt, so much the spirit calms as rum and true religion.”- Lord Byron

From the mid-1800s, the Tobago sugar industry began to decline due to a combination of factors: the Emancipation of slaves, a disastrous hurricane in 1847 and the Sugar Depression of the 1880s and 1890s when sugar prices fell sharply due to competition from European beet sugar. This new way of processing sugar led to the collapse of Tobago’s sugar economy.

Labour declined, planters continued production by investing in machinery with steam engines. In addition, plantation owners moved their estate closer to the production area to manage its labour efficiency.

With rum also came the revolution. It wasn’t until the end of slavery, the sugar beet business grew exponentially, along with environmental changes that eventually supplanted the sugar cane sector in Tobago. The many wars fought over rum are told in the history books of many nations. From pirates to pubs, everywhere sugar and its by-product rum were precious. Although Tobago’s history of sugarcane is short compared to the other Caribbean islands, in Tobago, enslaved Africans and other indentured labourers fought for and secured de facto rights to own property. However, the colonists quickly transitioned from slavery to unpaid labour by establishing markets and producing provision grounds. These were places where the enslaved people asserted their dignity, enterprise, and desire to accumulate wealth.

Despite its infamous relationship with sugar, rum is produced worldwide with different variations and characteristics depending on the ingredients and the region. Rum distilled in two forms can be light or dark, and for this reason, rum’s differences and complexities add to its desirability. The light is fresh and fruity, and its darker version, a liquid gold so potently concocted that it could bring the most muscular men to their knees.